All Homicides are not Murders

No one at the scene that September night had any doubt someone had murdered the young man lying by the side of a country road. The round hole just right of his sternum said a bullet had killed him, but there was no gun to be seen. The coroner’s definition of homicide applied to the death of Samuel Algarin: another person had killed him. All homicides are not murders, but this one was. The District Attorney charged his killer with murder and a judge sentenced him to life in prison without parole.

His friend shot 18-year-old Daryl Perry while playing with a firearm they didn’t think was loaded. The same coroner ruled that a homicide too. After their investigation, the D.A.’s office charged the 20-year-old shooter, a former high school football star, with involuntary manslaughter, not murder.

A coroner or medical examiner decides if a death is a homicide. The criminal justice system — police and prosecutors — decide whether that homicide is a murder and what criminal charges, if any, they will file. In these two homicides, for example, law enforcement charged the two shooters with very different crimes.

Judicial executions (capital punishment) are homicides but not murders in the eyes of the criminal justice system. A soldier’s death in battle is a homicide too, but it’s rarely a crime.

“We are not interested in whodunit, all we want to know is what did it.”

Dr. Milton Helpern

Homicide and the Murder Trial

In other words, homicide is a neutral term in medicolegal death investigation. It simply means that the death happened because of the action of a person other than the decedent. It doesn’t denote a crime or intent to kill. That’s why all homicides are not murders. Intent to do harm, while critical to legal decisions about criminal charges, plays no role in the coroner’s decision to call a death a homicide. Pioneering forensic pathologist Dr. Milton Helpern once said, “We are not interested in whodunit, all we want to know is what did it.”

Most people — including many jurors in homicide trials — don’t understand the distinction between the medicolegal definition of homicide and that of the criminal justice system. Lawyers for the prosecution may take advantage of that ignorance. Here’s an exchange this author experienced as a witness in a murder trial.

“What was the manner of death you put on the death certificate?” asked the Associate District Attorney.

“Homicide,” the coroner replied.

“No further questions,” said the ADA.

This was the point in the trial where it “might also be beneficial for defense attorneys to specifically question the expert about the meaning and limitations of the medical examiner’s ‘homicide’ designation.” In this case, the defense attorney didn’t take advantage of the opportunity to inform the jury that all homicides are not murders.

Location Matters

If someone is shot in Chester County but dies in another county, the coroner where the person dies has jurisdiction over the medicolegal death investigation. But Chester County’s law enforcement officials would have jurisdiction over the shooting because that’s where the injury happened. They would have to work with the other county’s coroner on the case.

Jurisdictional mismatches like this mean that the number of homicides reported by a District Attorney will not always match the number reported by the coroner in the same county. The D.A. counts homicides where the original injury occurred in their county, while a coroner counts homicides she investigates and certifies, regardless of where the original injury occurred.

Time and Age Don’t Matter

A recent prison death in Delaware County was ruled a homicide, but the death was said to be due to a gunshot injury that occurred before the man was jailed. Details haven’t been released by the County, so we don’t know the interval between the shooting and the death.

A common example of a delayed homicide is when someone dies years after injuries sustained in an assault by another person. The assault may have paralyzed the person who later died of delayed complications like sepsis from skin or bladder infections. If the coroner knows about the assault, she will likely rule it a homicide. The challenge is finding out when and where the assault took place. That information is needed for the death certificate and so law enforcement in the correct jurisdiction can be notified of the death.

Reports of children, even toddlers, shooting a sibling or other family member are no longer rare. A coroner will rule these tragic cases homicides, though they are more often due to negligence on the part of parents than intent on the part of the child. But it’s unusual for prosecutors to file first- or second-degree murder charges in such cases. For example, the District Attorney charged a Montgomery County, PA 13-year-old who shot and killed his 12-year-old sibling with third-degree murder.

How Many Homicides are there?

Some county coroners and medical examiners in Pennsylvania see many homicides every year, while others see very few. But the lack of transparency in most Pennsylvania counties, especially on the part of coroners and medical examiners, limits what we know. According to a 2022 state survey of C/ME offices, less than 20% of Pennsylvania’s 67 coroners post statistical data or an annual report on their website.For example, a police dashboard claims Philadelphia had 562 homicides in 2021, but there are no statistics on the Medical Examiner’s website. A state crime dashboard likewise relies on data from law enforcement sources, but no comparable state coroner/medical examiner dashboard exists.

Pennsylvania’s Violent Death Reporting System (part of the Department of Health) has access to death certificates from all 67 coroners, but the most recent homicide data available is for 2019. That data is limited to total state numbers and numbers for the two largest counties — Allegheny County (Pittsburgh) and Philadelphia.

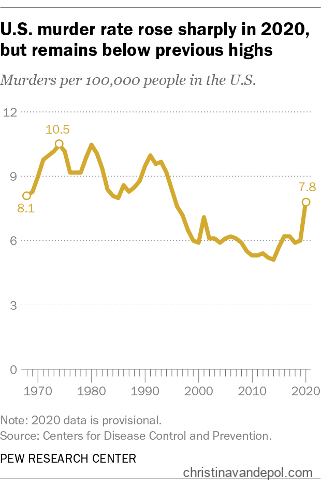

The National Violent Death Reporting System (CDC) combines coroner/medical examiner data from death certificates and law enforcement data. Both sources showed a big increase in homicides in 2020 compared with 2019. The rate of homicides per 100,000 people increased from 6.0 to 7.8. It increased again in 2021, but was trending back down in 2022. Historically, however, rates have been trending downward since the early 1990s.

How CDC Handles Homicide Statistics

Strangely enough, CDC lists homicide as a cause of death in its statistical databases and analyses. How does that happen? Coroners use words, medical terminology words, on a death certificate. A computerized system assigns an ICD-10 code to that terminology. It might, for example, code “Gunshot wound to the head” as X93. X93 is what goes into the database. A search of those codes counted as homicides includes the following examples:

- Y01: assault by pushing from a high place

- Y04: assault by bodily force

- X93: assault by handgun discharge

- X94.0: assault by shotgun

- X95.02: assault by paintball gun discharge

Various types of firearms — mostly codes X93-X95 — are by far the most common causes of homicide in the United States. In 2020, firearms were involved in 79% of homicides. In 2021, an estimated 20,000 people died of a firearm-related homicide.