Intimate Partner Violence and Murder-Suicides

The recent tragic death of Dr. Beth Frost in Dallas, TX, was eerily similar to many of the homicides she must have investigated as a medical examiner: Female murdered by a male partner. History of conflict with that partner. Female trying to exit the relationship. Death by firearm. Suicide of the shooter.

Stephanie (Burtnett) Williams was shot in the head and chest by her husband in their suburban Chester County (PA) home, after which he shot himself. The 2018 murder-suicide followed a long history of intimate partner abuse. Stephanie’s death happened while she was trying to get a Protection from Abuse order.

Barbara Palladino died in her Chester County (PA) home in 2019 of multiple shotgun wounds to the head. The shooter, a boyfriend of 10 years, died at the scene of a self-inflicted shotgun wound. Reportedly, he had become suspicious she was going to end the relationship because of financial conflict.

They are only a few of the hundreds of women killed by men in murder-suicides in the United States in the past few years alone. Murder-suicide is common in intimate partner violence-related deaths. This article identifies what we know (not a lot) and don’t know about these tragic events. Significant gaps remain in the data and the research on domestic violence (DV), intimate partner violence (IPV), and murder-suicide. Closing these gaps will save lives.

Note: The data show that women are disproportionately the victims and men disproportionately the perpetrators in IPV murders and especially murder-suicides. This article therefore uses she/her pronouns for victims and he/his pronouns for perpetrators.

Where’s the Data on Intimate Partner Homicides?

Reliable statistics on intimate partner violence, and especially homicides, are hard to come by. This is true at the local, state, and national level. In Pennsylvania, for example, a state-wide study found that very few Pennsylvania coroners make death statistics of any kind available on a website or in an annual report. Furthermore, “Pennsylvania doesn’t have reporting requirements for domestic violence homicides” according to a report from the Pennsylvania Coalition against Domestic Violence (PCADV). So, even though Pennsylvania recently began reporting violent deaths in general to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), those reports may not include information on whether domestic or intimate partner violence factored into a homicide or suicide.

On the national level, the CDC only recently succeeded in getting all 50 states plus the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico to participate in the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS). As a result, the most recent NVDRS report includes data from only 27 states. That report found that “…among female decedents the suspect was most frequently a current or former spouse/intimate partner (51.4%)”. Another 21.5% were killed by a child, parent, or other relative. In other words, DV accounted for almost 80% of the women murdered in the United States seven years ago.

Non-governmental organizations like the Violence Policy Center have attempted to step into the information gap. It publishes what is probably the most comprehensive (maybe the only) data on murder-suicides in the United States. Their 2020 report (American Roulette) found that 640 people lost their lives in a murder-suicide event in just the first half of 2019. Two-thirds of those events were IPV-related. Among the IPV-related events, 95% of the homicide victims were female and 92% involved guns.

Violent Death Data in Pennsylvania

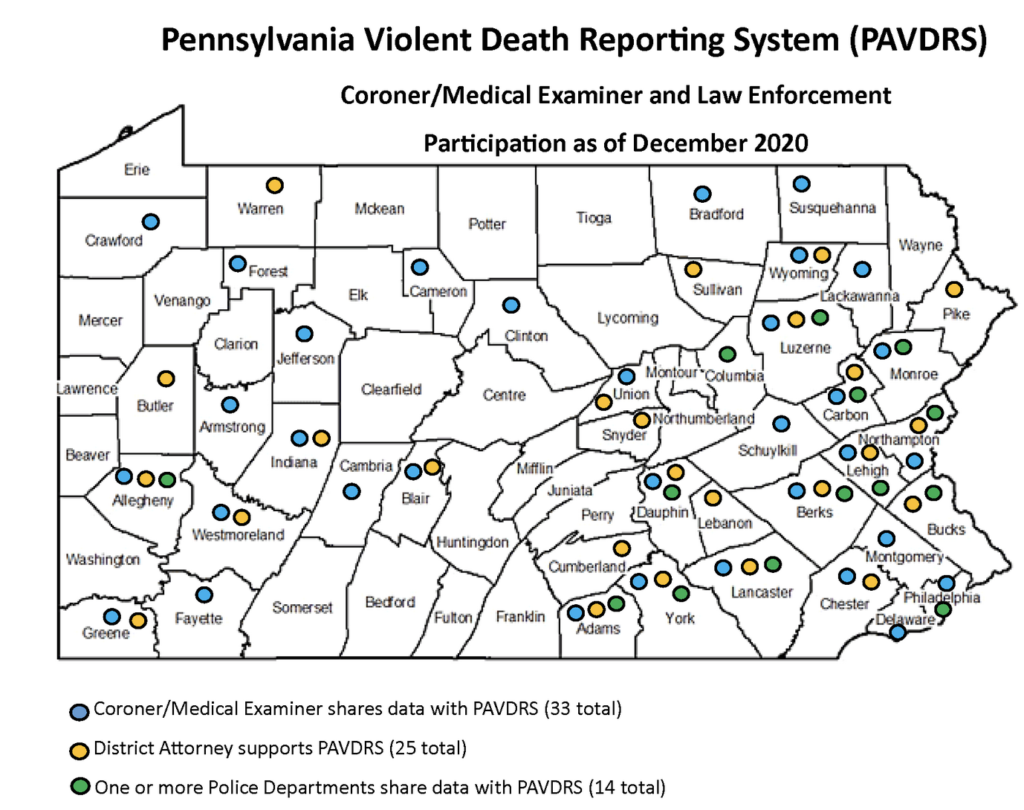

Violent death data starts at the source, which always includes a coroner or medical examiner. For example, the Pennsylvania Violent Death Reporting System (PAVDRS) collects data from death certificates, coroners/medical examiners, and law enforcement agencies. However, participation is voluntary and not all county coroners, medical examiners, or law enforcement agencies participate. In fact, as of December 2020, only half of PA’s coroners/medical examiners were providing data to the PA VDRS (Figure 1).

Multiple factors, including a decentralized death investigation system, lack of coroner resources and funding, and a dysfunctional relationship between coroners/medical examiners and the PA Department of Health may account for this lack of participation.

The following policy changes could improve reporting of DV/IPV-related deaths in Pennsylvania and elsewhere:

- Add DV/IPV checkbox (similar to the Pregnancy Checkbox) to the death certificate

- Implement a domestic violence reporting form for coroners/medical examiners

- Compensate coroners (per report) for DV reports submitted to VDRS

- Increase Act 122 funding (death certificate fees) to coroners/medical examiners

Suicide and Intimate Partner Homicide

Law enforcement and prosecutors often consider confirmed or obvious murder-suicides as “case closed.” Because there is no one to charge with a crime, little or no further investigation takes place. Coroner inquests, unfortunately used by only a few PA coroners anymore, would be an excellent tool for in-depth investigation and understanding of these deaths.

Since approximately 90% of shooters in these events are male, it makes sense to look more closely at those perpetrators. Tony Salvatore did so in his recent review of domestic violence murder-suicides in the FBI’s Law Enforcement Bulletin. As a consequence, he argues that suicide, not homicide, may be the motivating factor in many of these murder-suicides. It follows that suicide prevention efforts should include this population.

The Violence Policy Center draws a similar conclusion. Its 2020 report suggests passing “stronger domestic violence legislation …, including programs that assist men with coping with issues of anger, control, and separation.”

What Else can We do?

Almost half of female homicide decedents were aged 20-44 years, according to the NVDRS. Undoubtedly, women’s relationships with their eventual killers sometimes begin during the teen years. Middle school, if not earlier, is when education about DC and IPV violence should begin. Yet some states, including Pennsylvania, don’t have a sex-education requirement. PA House Bill 1335 (2021-2022) would have included trauma-informed information about domestic violence and intimate partner violence, but never made it out of the Education Committee.

Outside the formal education system, local groups like the Domestic Violence Center of Chester County provide an excellent model. They offer community-based educational and prevention programs, focusing on tweens, teens, law enforcement officers, and health care providers.

Finally, although the role of guns in DV/IPV deaths is indisputable, that complex and controversial topic is beyond the scope of this blog. But the Violence Policy Center sums it up well: “To reduce lethal violence against women, it is essential to keep guns away from domestic abusers.”

***

Hotlines – Domestic Violence

Chester County, PA: 888-711-6270 or 610-431-1430

National: 1-800-799.SAFE (7233)

Hotline – Suicide or Emotional Distress

988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline

***