Hundreds, probably thousands, are dying heat-related deaths in 2023. It’s up to physicians, coroners, and medical examiners to more diligently investigate and document deaths due to this silent killer. My June 2022 blog post recommendations for heat-related death investigation haven’t changed, but the urgency around these and other climate-related deaths has drastically increased.

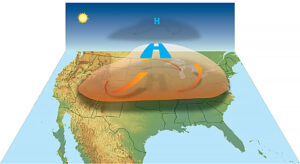

Heat domes

On August 22, 2023, a heat dome covering almost half of the United States raised temperatures in Minneapolis, MN, as high as 113º F. It’s only a matter of time before heat domes get names, like hurricanes.

In Phoenix, AZ, a city accustomed to excessive heat—it even has a heat tsar—, temperatures exceeded 110º F (43ºC) the entire month of July. By mid-August, the medical examiner’s office had confirmed 89 heat deaths in Maricopa County (Phoenix is the county seat), with hundreds more cases pending investigation.

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a heat and health tracker where you can search past, current, and projected county-level data. I entered Harris County, TX (includes Houston) in the search box and learned that it has had 90 days of temperatures above 90ºC so far this year, has a current temperature of 102.3ºC, and a forecast of one (1) day of extreme heat (temperature above the historical 95th percentile) for next month.

Heat: A silent invisible killer

A recent article in The Atlantic by hospital pathologist Benjamin Mazer points how difficult, even impossible, it can be to know if heat was a factor in someone’s death. If someone with known heart disease or chronic renal failure dies during a heat wave, did heat stress overwhelm their already-compromised organs or was it just a coincidence? This diagnostic uncertainty is one reason death certificates aren’t accurate sources for tracking heat-related deaths.

When a medicolegal office does get involved in a heat-related death, it’s usually because that death is sudden, unexpected, or happens outside a medical facility. Then, as part of the scene investigation, the C/ME may document hyperthermia, excessive exposure to the heat, or even get reports that the decedent had symptoms of heat stroke.

Most C/ME jurisdictions don’t have clear laws at this time regarding natural disaster/climate-related death investigation. In Pennsylvania, for example, the only type of death that might result in a heat-related death investigation is “a sudden death not caused by a readily recognizable disease…” (16 P.S. § 1218-B).

A medicolegal death investigation can help determine whether a death was directly or indirectly related to heat exposure. Direct causes like heat stroke go on Part 1 of the death certificate. If heat didn’t directly cause the death but was a contributing factor, the coroner should mention that in Part 2 of the death certificate. In addition, the best practice now is to mention the specific heat event either in Part 2 (for natural deaths) or in the injury section (accidental deaths).

Who’s at risk for heat-related death?

Farmworkers Cruz Urias Beltran, age 52, and Sebastian Francisco Perez, age 38, both died of heat-related causes in 2021, Beltran in Nebraska and Perez in Oregon. They’re two of hundreds: those who work outdoors are among the most likely to become victims of climate disasters, including heat waves.

Certain populations are more vulnerable to environmental heat than others. A 2022 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association (Khatana et al.) found that over a 10-year period in the United States, extreme heat was disproportionately associated with deaths of older adults, men, and non-Hispanic Blacks. Why the elderly? They’re less able to regulate body temperature and they are more prone to dehydration. They’re also more likely to be on medications like diuretics, heart, and high blood pressure drugs that inhibit normal body responses to excessive heat. Why men? Perhaps because they are more likely to work outdoors in physically demanding jobs. Why Blacks? Perhaps because of urban heat islands and socioeconomic factors. We need more data.

The poor are at greater risk for several reasons. Air conditioning costs money, and if you can’t afford the air conditioner or the utility bills, a heat wave can be deadly. That’s what happened to Ramona and Monway Ison, a couple living in a trailer in Baytown, TX, who died of heat exposure earlier this summer. Chronic health conditions or unaffordable treatments for those conditions are another risk factor, as is working manual labor jobs like cooking, construction, or agriculture.

Tracking heat-related deaths

Tracking heat-related deaths may be even more inaccurate and controversial than tracking COVID-19-related deaths. Nationally the numbers come from CDC which abstracts them from death certificates using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Version (ICD-10) codes. X30, for example, is the ICD-10 code for excessive heat exposure. From 1999 through 2020, CDC found that excessive heat was a direct or contributory cause of an average of 1309 deaths annually.

But as a report in Stat argues, the “true number could be as high as 30,000, especially in a year like 2023.” The report claims that death certifiers often fail to consider or record excessive heat as a contributory factor in Part 2 of the death certificate.

For a model of excellent heat-related death tracking, look at Maricopa, Arizona. Its Medical Examiner’s Office does painstaking investigations and classifies suspected cases as heat-caused (Pt 1 of the death certificate), heat-related (Pt 2), or suspected/under investigation (pending).

The future

The U.S. Global Change Research Project has estimated that the number of heat-related deaths in U.S. cities will increase by “thousands to tens of thousands” over the remainder of the twenty-first century. The good news is that there could be fewer fatalities depending on how humans adapt to increased temperatures, both physiologically and by use of air conditioning or other technologies. To that end, CDC’s Climate and Health Program provides support and grants for adaptation to a changing climate. The big fix, of course, is reducing the projected increase in global temperatures. Keep planting those trees.

Here in Denver, we’ve had too many days in the high 90s this summer. At our elevation of >5000 feet, we get an intense solar hit. We can almost feel our skin being singed on a hot summer day.

I know firsthand the symptoms of heat exhaustion and have learned to quickly stop my outdoor activity (for me, this often is gardening for too long on a hot day). Moving to a cool shady area (preferably inside), resting, sips of water are mandatory. The CDC has an excellent summary of heat-related conditions (heat stroke, heat exhaustion, heat rash …). A must-read document in this time of climate change!

If you want to read more about the terrifying effects of extreme heat, google Phoenix and persons hospitalized with third-degree burns from falling on asphalt that’s as hot as the burners on your stove turned on “high”.